Chevron Attacked the Very Idea of America

Representative Government vs. the Priesthood of Experts

by Rod D. Martin

July 4, 2024

The Supreme Court’s overturning of Chevron was an early Independence Day gift. Chevron stood for an imperial bureaucracy, neither responsible to the people nor accountable to anyone, a priesthood of experts pursuing what Thomas Sowell called “the vision of the anointed”, interpreting, adjudicating, and above all, making the laws we must live by, however they saw fit.

Last week, in their Loper Bright and Jarkesy rulings, the Court overturned that half-century travesty, partly upending the statist technocratic order and, at least to a degree, replacing it with the Constitutional vision of the Founders.

James Madison would be proud.

The Administrative State: Subject-Matter Dictatorships

To understand the principles at stake, we first must grasp the radical shift in governance represented by the advent of the administrative state a century ago.

The Founding Fathers established responsible government: elected leadership that must regularly stand accountable for its actions and their effects. Their Revolution explicitly repudiated the idea of lawmaking and enforcement by far-away elites, in favor of that government which was closest to the people. They recognized the benefit of continent-wide (though not unelected or transoceanic) policy on a handful of key issues; but to achieve that, they created multiple competing elected bodies to check each other’s hubris, and they wrote a Constitution that restricted their new government to only a short list of subjects.

Why did they do this? Because they had experienced the tyranny born of unrestricted arrogance. And while they knew they couldn’t change the nature of man, they could use competition among men to restrain their more venal and predatory impulses.

They thus also created a very small bureaucracy, every part of it directly accountable to one or more elected officials. With no Civil Service Act, and a Senate elected by the state legislatures, if your mailman kicked your dog you could go find your state representative at the coffee shop and complain. Enough complaints and change was certain: elected officials have a lot of incentive to listen.

Over time, usually for practical reasons but increasingly motivated by a very real shift in philosophy, not only did government grow exponentially, but elected officials became both more remote and less able to help. We decided we wanted to “protect” bureaucrats from the “spoils system”, so we made it nearly impossible for Presidents to fire them. We decided to delegate vast authority to those bureaucrats, people whose only constituents, aside from their current bosses, were the companies and interest groups who might hire them later. We did this in the name of “nonpartisanship” and “expertise”.

By the end of the New Deal, we’d curbed representative government at every point, in favor of a permanent unelected elite. And while we did not create a true unitary state as other countries did in the 1930s, we did establish a sea of subject-matter dictatorships: unaccountable entities with nearly unlimited power in their assigned areas.

Take the Environmental Protection Agency as one example. Created by a hodgepodge of executive orders and bits of bills, there is no single enabling act to which one can refer for a clear grant of or limit on its power. Yet the EPA, like countless other agencies, concentrates the powers of all three branches of government in its agency administrator, the de facto dictator. The agency makes law, and its lawmakers work for the administrator. The agency enforces the laws that it makes, and those enforcers also work for the administrator. Worse still, the agency employs a small army of Administrative Law Judges, or ALJs, none of them confirmed by the Senate, whom it may haul you in front of whenever it chooses. They work for the administrator too.

All of this is a grossly unconstitutional violation of the separation of powers. It eliminates virtually all checks and balances. And the Chevron Court acknowledged that, to a degree: it said that by 1984, things had been done this way so long that it would just be too disruptive to change things.

In short, Chevron established constitutionality by longevity. You can apply that logic to Plessy v. Ferguson and tell me whether you think it’s a good idea.

Jarkesy and Juries, the Bulwark of Your Liberty

But Chevron did more and worse still. Chevron largely eliminated your Seventh Amendment right to a jury trial, by almost completely curtailing your right to appeal an ALJ’s ruling to an actual, Constitutionally-authorized Article III court.

Let’s say that again: under Chevron an agency could sue you in front of its own judges, over its own made-up rules, enforced by its own bureaucrats, and you had no right to an appeal. You didn’t even get a jury of your peers.

That last bit is the keystone, the philosophical crux, of the entire matter. It is the core of the disagreement between King George and George Washington, between Madison and Marx.

The bureaucrats argue, as do the Democrats shrieking over Chevron’s overthrow, that the subject matter addressed by the various agencies is so complex, so intricate, so specialized that not only can a jury not understand, neither can an Article III federal court. They tell us in more-and-more blatant terms that, though they constantly pursue rule by unelected judges, even those experts are insufficiently elite. For true “democracy”, we must have rule by a class of super-experts, not subject to any oversight at all.

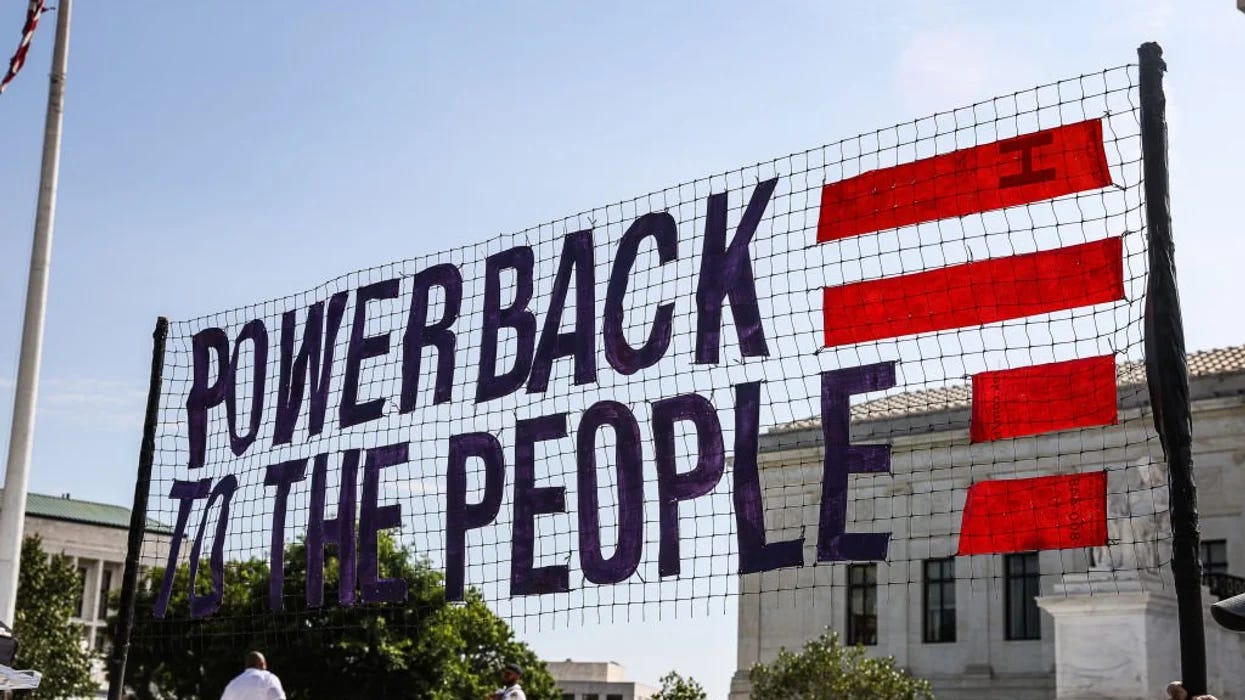

At every step of the process, Chevron replaced “government by the people” with that priesthood of experts, those who must simply be trusted to be benevolent, all-knowing and true. This is the technocrat’s and socialist’s (but I repeat myself) dream: to eliminate the great unwashed from the process of scientific government.

And if federal judges are too unwashed for our would-be betters, how much more so juries?

But juries matter, and not just because they are constitutionally guaranteed. Judges apply the law, but juries establish the facts: what happened, what didn’t, who’s believable, who’s not. There’s a reason for “of your peers”. The most basic fact which must be established is whether or not the accused had any intent to commit the act for which he’s being prosecuted. The priesthood, far removed from your life experience, is poorly positioned to determine that; your peers can stand in your shoes and imagine themselves in the same situation.

Your jury can also nullify a law they believe to be unjust.

Agency employees, regardless of their title, aren’t going to do that. Most of the time, you’re just going to lose, either outright or through a settlement. And if no appeal is possible, there’s no incentive for the priesthood to be reasonable, not in making law and not in its adjudication. After all, who the heck are you?

It’s worse. Increasingly, agency regulations are “strict liability”, which means that your intent doesn’t matter. By this standard, an accidental killing becomes murder. And speaking of murder, agencies issue not just civil but their own criminal laws, by some estimates as many as 300,000 separate agency-made offenses, all adjudicated solely by their own ALJs with no juries and no possibility of appeal.

Last week, in SEC v. Jarkesy, the Supreme Court upended that, re-establishing your Sixth and Seventh Amendment rights. And the Democrats’ howling began.

Loper Bright and the Abomination of “Chevron Deference”

But the crying was about to get louder. The very next day the Supremes handed down Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, and wiped out much of the rest of the philosophy back of Chevron.

Loper Bright is about so-called “Chevron deference”, the doctrine that if you somehow do get to an Article III court, that body must defer to an agency’s interpretation of any ambiguity in a law the agency enforces. Chevron deference didn’t just upend centuries of principles of statutory construction. It also neutered the Article III courts.

Again, this was a feature, not a bug. The three dissenting Democrat justices made that clear, by not focusing on the constitutionality (or lack thereof) of Chevron but rather lamenting the priesthood’s loss of power. Their philosophy is simple: the anointed “experts” should rule you. Peasant.

Freedom is impossible if those who wield force are not accountable to the people. But in David Harsanyi’s words, “bureaucrats do not function under a notion of ‘accountability’ that most normal people would recognize. When was the last time an agency cleaned house because its policies had failed? When was the time the administrative state was reined back in any genuine way? How many regulators or appointees are ever fired? If you were as bad at your job as Alejandro Mayorkas, you’d be out of work forever.”

Put more simply: what power do you have to make any of those things happen?

The Founders’ Vision vs. “Our Democracy”

When power is vested in the elected branches, as our Constitution requires, you have exactly that power every election. The Chevron philosophy is the opposite: technocratic at best, socialistic at worst, without accountability always.

But technocracy is failing, and losing legitimacy, everywhere. There’s a reason for the increasingly global populist revolt: the self-anointed elites have lost all touch with those they rule (and rule they do, not serve). George Friedman writes about this, and what he believes will come next, in his excellent The Storm Before the Calm. From a somewhat different direction so does Neil Howe, in his brilliant The Fourth Turning is Here.

The Founders answer was and surely would be smaller government; but even if they could not make government smaller, at the very least they would shift its power back to the elected branches and thus the election process. Give the President the power to replace bad personnel. Give individual House members and Senators enough staff to actually oversee the government we have. Force agencies to defend their “brilliance” before real, constitutional courts. Force Congress to actually legislate, rather than (unconstitutionally) delegating its powers to the bureaucracy.

It is this last bit where the Court failed, at least in part. In Jarkesy, the Fifth Circuit re-established the long-dead nondelegation doctrine 10-6: Congress must not delegate its law-making powers. This would have been the death of the Administrative State, not of the agencies or their enforcement duties but of their subject-matter dictatorships. The Supreme Court did not address that portion of the case, neither affirming it nor overruling it.

This is a shame. Hopefully it will be rectified next term, after the Beltway has had time to adjust to all of the foregoing.

The Founders’ vision gave us the America we know, the tiny colonies huddled along the Atlantic coast that in barely more than a century grew into the colossus of the world, by attracting millions to its opportunity and liberty, and by harnessing their talents “like an invisible hand” to create a near-universal prosperity unknown in all the history of man. Liberty is chaotic, and brilliant, and wildly innovative; and that innovation is called forth by a system that does not direct, but rather allows everyone to imagine the better future that would come from solving other people’s problems, and then doing so not through top-down coercion but through the marketplace.

For millennia, the aristocratic, elitist vision produced a stultified world, in which as late as 1800 fully 94% of humanity lived in extreme poverty, and in which the richest lived far worse than you do. Freedom has doubled life expectancy, put a supercomputer in the hands of billions, and upended tyrannies as old as the world.

But this century-old debate is far from over. Increasingly hostile to the Constitutional order our Founders gave us, Democrats believe technocracy is essential to what they call “Our Democracy”. They are increasingly clear that "Our Democracy" means a priesthood of experts, shielded from accountability or responsibility, making decisions "for the good of the people" without their involvement or consent.

In short, "Democratic Centralism".

Let the reader understand.

— This essay also appeared at ClearTruthMedia.com.